BIOMIMICRY IN DESIGN: 7 INCREDIBLE BUILDINGS INSPIRED BY NATURE

Nature has always been able to use its intelligence to adapt to change — selecting the most efficient traits to retain and discarding ones that aren’t. Biomimicry or biomimetics is the act of mirroring these features into human-made designs. The term is derived from the Greek ‘bios’, meaning life, and ‘mimesis’, which means to imitate.

In architecture, it can be adopted to create structures that look, operate, or co-exist with natural processes. There are three levels of biomimicry that designers can approach their creations with:

- ORGANISM: Design that replicates forms of the natural world.

- BEHAVIOUR: Design that replicates the behavioural nature of an organism.

- ECOSYSTEM: Design intended to be part of and replicate natural ecosystems.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF BIOMIMICRY

The first appearance of the term was found in ‘Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature’, a book released by scientist Janine Benyus. It details the concept of utilising biomimetics in order to solve environmental destruction.

In recorded history, humans have studied the dynamic between design and nature since the 1500s. The earliest known examination is when Leonardo da Vinci wrote ‘Codex Leicester’ — a book of his scientific theories, including how humans could model structures after birds in order to take flight ourselves.

The most notable example of biomimicry in modern times is the creation of velcro. During a hunting trip in 1948, Swiss engineer George de Mestral took his dog for a walk and noticed burrs that clung to his dog’s fur. Under a microscope, he analysed the tiny hooks that were able to firmly attach themselves to the dog and envisioned how that model could be replicated for human use.

Aside from product invention, biomimicry in design can be used to create structures reflecting the natural world’s intelligence. Below, we explore seven interesting examples of architecture inspired by nature.

1. BOSCO VERTICALE, ITALY

Architect: Boeri Studio

Bosco Verticale, translating to ‘vertical forest’, is a soaring set of buildings in Milan. The aesthetics are characterised by large, staggered balconies with a lush vegetation facade.

There are over 900 trees, 5000 shrubs, and 11,000 perennial plants, which help to combat smog in the city. It’s estimated that almost 20,000 kgs of carbon are converted each year. Bosco Verticale is an example of ecosystem biomimicry, as the biodiversity in each building manages to attract new bird and insect species into Milan.

The dense inclusion of plants creates a shade and protection barrier from wind and sun, naturally moderating temperatures in the summer and winter seasons. Furthermore, it shields interiors from noise pollution and dust from metropolitan traffic.

The self-sufficient towers use solar panels and filtered wastewater to keep plants hydrated, thus reducing the carbon footprint. The project is considered to be one of the most innovative ways to combat urban sprawl while promoting ecological health.

2. BIRD’S NEST STADIUM, CHINA

Architects: Herzog & de Meuron

Strikingly modern, you may recognise this building from the 2008 Beijing Olympics. It was designed specifically for that event and remains a sporting and architectural wonder for visitors today.

It displays biomimicry in design through an exterior that features intricate steel cladding, taking a similar form to the building’s name — bird’s nests. Beijing Olympics organisers desired a sustainable focus, which is why steel was chosen, as it is easily recyclable. Besides aesthetics, the design reinforces a biomimetic approach as ethylene tetrafluoroethylene (ETFE) panels were infilled between the steel gaps, offering shelter from the elements and soundproofing. This concept mimics how birds fill the nest with twigs and other collected materials to create insulation.

ETFE panels weigh about 1% of their glass counterpart and allow more light in, which permitted the daring design of the stadium. Additionally, they are highly durable and self-cleaning, meaning that when wind and rain come into contact, it is more efficient at removing dirt from the surface.

3. ONE ONE ONE EAGLE STREET, AUSTRALIA

Architects: Arup, Cox Architecture

In Brisbane’s ‘Golden Triangle’ precinct is One One One Eagle Street — a 57-storey office building that’s bringing a biomimicry edge to Australia’s fastest-growing city.

The design was inspired by the way plants grow upwards towards the sun. Dealing with space constraints, the team who created the structure had to find ways to land the columns as the current site couldn’t allow them to be spaced evenly. So engineers looked into ways that columns could branch out as the building rose. As the design developed, it started looking more and more like a plant. From there, they read studies about how germinating seeds moved towards the light and infused that patterning into the building.

At about 20% of the way through, Ian Ainsworth from Arup stated that “…we had inadvertently started mimicking the fig trees across the road from the site.”

Incorporating the Moreton Bay fig trees into the building’s design was an impressive quality that reflected the historic flora of Brisbane and an inspiration source to overcome spatial challenges.

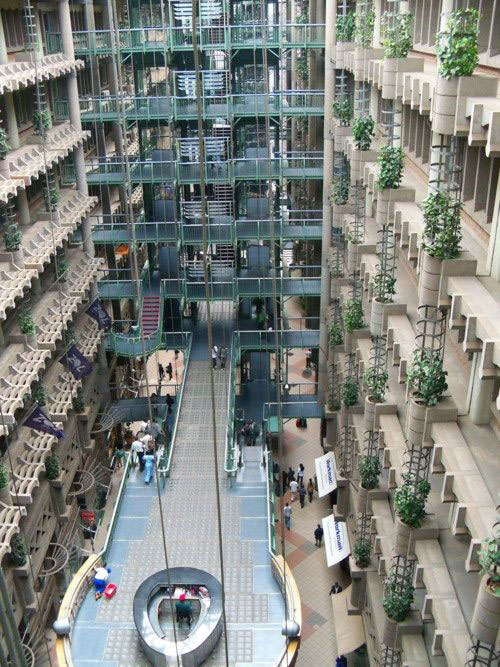

4. EASTGATE CENTRE, ZIMBABWE

Architect: Mick Pearce

The Eastgate Centre in Harare, Zimbabwe, is an impressive example of biomimicry in design. The shopping centre and office space was built in 1996 and uses passive and energy-efficient processes to ventilate and cool the building. Architect Mick Pearce studied the chimneys and tunnels of termite dens for inspiration when creating Eastgate’s design. Termites are adept at regulating the inside of their dens at a comfortable 30°C amidst daily fluctuating temperatures of 0–40°C.

This concept was applied to the 31,000 square-metre establishment, whereby cool air is pulled in overnight and stored in concrete blocks at the base of the building — similar to the way soil in a termite mound acts. Fans throughout the centre distribute the cool air. Once the air begins to warm, it exits the building through a central atrium.

Because Eastgate was built without air conditioning, it cost 10% less to build than a structure of similar dimensions while using around 90% less energy to regulate the internal temperature.

5. BIQ HOUSE, GERMANY

Architects: Splitterwerk, Arup

Have you ever looked at algae and wondered how it could be used in design? Well, the team from Arup did and partnered with architectural firm Splitterwerk to make it happen.

BIQ House in Germany adopts biomimicry by including algae in a clever facade system. 200 square metres of panels create a greenhouse environment for the algae to thrive. Liquid nutrients and carbon dioxide is circulated throughout the facade in order to keep the algae healthy.

Once sunlight hits the exterior, the algae multiply and offer the building a source of shade. As the algae grows over time, it gets harvested and fermented in order to create biogas which helps to power the building. It produces five times as much biogas as land plants.

6. FLOR DE VENEZUELA, VENEZUELA

Architect: Fruto Vivas

Flor de Venezuela was built for Expo 2000, an international fair held in Hanover, Germany. It showcased visions from 155 countries that centred around the theme of ‘Humankind – Nature – Technology’, in particular, how humans can employ technology to work congruously with nature.

Venezuela’s entry was a kinetic building that provided shelter for expo entrants. Fruto Vivas designed the structure, taking inspiration from table-top mountains in the Gran Sabana region, but mainly Venezuela’s national flower — the orchid.

The glass building was topped by a 16-petal flower, with each petal around 10 metres long. The moving frame was controlled by a hydraulic system that permitted the petals to open and close. It provided a dynamic visual aesthetic to the building but also a functional one — when weather wasn’t desirable, the petals could be closed, hugging the building to keep out wind and rain.

Flor de Venezuela now resides in Barquisimeto, Venezuela.

7. THE GHERKIN, ENGLAND

Architects: Arup, Norman Foster

An icon of London’s skyline, 30 St Mary Axe, or informally, The Gherkin, is a building in the heart of the financial centre.

The building was inspired by the design of Venus’ flower basket — a sea sponge found in the deeper parts of the Pacific Ocean. It’s able to withstand considerable depths due to its lattice exoskeleton and conical shape, which provides stability against strong currents.

Following a diagonal lattice pattern, The Gherkin has a sustainability focus by including natural ventilation. Gaps in flooring allow air to circulate between levels, and each level has six atria that span across five floors — only interrupted at every sixth floor as a firebreak.

The air moves through the double-layered facade, which creates a double-glazing effect and insulates the building through passive heating and cooling. In return, The Gherkin uses around 50% of power than that of a similarly-sized building.